Archive for the ‘Info Kesehatan’ Category

Although rapid gains in life expectancy followed social change and public health measures, progress in the other medical sciences was slow during the first half of the 20th century, possibly because of the debilitating effect of two major world wars. The position changed dramatically after World War II, a time

that many still believe was the period of major achievement in the biomedical sciences for improving the health of society. This section outlines some of these developments and the effect they have had on medical practice in both industrial and developing countries. More extensive treatments of this topic are

available in several monographs (Cooter and Pickstone 2000; Porter 1997;Weatherall 1995).

Epidemiology and Public Health

Modern epidemiology came into its own after World War II, when increasingly sophisticated statistical methods were first applied to the study of noninfectious disease to analyze the patterns and associations of diseases in large populations. The emergence of clinical epidemiology marked one of the most important successes of the medical sciences in the 20th century. Up to the 1950s, conditions such as heart attacks, stroke, cancer, and diabetes were bundled together as degenerative disorders, implying that they might be the natural result of wear and tear and the inevitable consequence of aging. However, information about their frequency and distribution, plus, in particular, the speed with which their frequency increased in association with environmental change, provided excellent evidence that many of them have a major environmental component. For example, death certificate rates for cancers of the stomach and lung rose so sharply between 1950 and 1973 that major environmental factors must have been at work generating

these diseases in different populations. The first major success of clinical epidemiology was the demonstration of the relationship between cigarette smoking and lung cancer by Austin Bradford Hill and Richard Doll in the United Kingdom. This work was later replicated in many studies, currently, tobacco is estimated to cause about 8.8 percent of deaths (4.9 million) and 4.1 percent of disabilityadjusted

life years (59.1 million) (WHO 2002c). Despite this information,the tobacco epidemic continues,with at least 1 million more deaths attributable to tobacco in 2000 than in 1990, mainly in developing countries.

The application of epidemiological approaches to the study of large populations over a long period has provided further invaluable information about environmental factors and disease. One of the most thorough—involving the follow-up of more than 50,000 males in Framingham, Massachusetts—

showed unequivocally that a number of factors seem to be linked with the likelihood of developing heart disease (Castelli and Anderson 1986). Such work led to the concept of risk factors, among them smoking, diet (especially the intake of animal fats), blood cholesterol levels, obesity, lack of exercise, and

elevated blood pressure. The appreciation by epidemiologists that focusing attention on interventions against low risk factors that involve large numbers of people, as opposed to focusing on the small number of people at high risk, was an important advance. Later, it led to the definition of how important environmental agents may interact with one another—the increased risk of death from tuberculosis in smokers in India, for example. A substantial amount of work has gone into identifying risk factors for other diseases, such as hypertension, obesity and its accompaniments, and other forms of cancer. Risk factors defined in this way,and fromsimilar analyses of the pathological role of environmental agents such as unsafe water, poor sanitation and hygiene, pollution, and others, form the basis of The World Health Report 2002 (WHO 2002c), which sets out a program for controlling disease globally by reducing 10 conditions: underweight status; unsafe sex; high blood pressure; tobacco consumption; alcohol consumption; unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene; iron deficiency; indoor smoke from solid fuels; high cholesterol; and obesity. These conditions are calculated to account formore than one-third of all deaths worldwide.

More recent developments in this field come under the general heading of evidence-based medicine (EBM) (Sackett and others 1996). Although it is self-evident that the medical profession should base its work on the best available evidence, the rise of EBM as a way of thinking has been a valuable addition to the development of good clinical practice over the years. It covers certain skills that are not always self-evident, including finding and appraising evidence and, particularly, implementation—that is, actually getting research into practice. Its principles are equally germane to industrial and developing countries, and the skills required, particularly numerical, will have to become part of the education of physicians of the future. To this end, the EBM Toolbox was established (Web site: http://www.ish.ox.ac.uk/ebh.html). However, evidence for best practice obtained from large clinical trials may not always apply to particular patients; obtaining a balance between better EBM and the kind of individualized patient care that forms the basis for good clinical practice will be a major challenge for medical education.

Source: David Weatherall, Brian Greenwood, Heng Leng Chee, and others. Science and Technology for Disease Control: Past, Present, and Future Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. Oxford University Press,2006. p.119

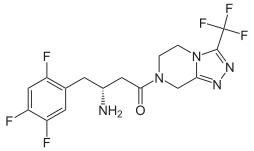

New Antidiabetes Oral

Posted on: Januari 18, 2009

Sitagliptin (INN; previously identified as MK-0431, trade name Januvia) is an oral antihyperglycemic (anti-diabetic drug) of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor class, Sitagliptin being the only 2nd Generation DPP4 inhibitor currently available. This enzyme-inhibiting drug is used either alone or in combination with other oral antihyperglycemic agents (such as metformin or a thiazolidinedione) for treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2. The benefit of this medicine is its lower side-effects (e.g., less hypoglycemia, less weight gain) in the control of blood glucose values. Exenatide/Byetta is an alternative drug that also works with the incretin system.

Adverse effects

In clinical trials, adverse effects were as common with sitagliptin (whether used alone or with metformin or pioglitazone) as they were with placebo, except for extremely rare nausea and common cold-like symptoms..[2] There is no significant difference in the occurrence of hypoglycemia between placebo and sitagliptin.[2]

History

Sitagliptin was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on October 17, 2006[3] and is marketed in the US as Januvia by Merck & Co. On April 2, 2007, the FDA approved an oral combination of sitagliptin and metformin marketed in the US as Janumet.

Mechanism

See also: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

Sitagliptin works to competitively inhibit the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4). This enzyme breaks down the incretins GLP-1 and GIP, gastrointestinal hormones that are released in response to a meal.[4] By preventing GLP-1 and GIP inactivation, GLP-1 and GIP are able to potentiate the secretion of insulin and suppress the release of glucagon by the pancreas. This drives blood glucose levels towards normal. As the blood glucose level approaches normal, the amounts of insulin released and glucagon suppressed diminishes thus tending to prevent an “overshoot” and subsequent low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) which is seen with some other oral hypoglycemic agents.

Source : wikipedia.org

Komentar Terbaru